The silence of Xi Zhongxun

Some investigative digging into the Tiananmen protests of 1989, from Joseph Torigian's new bio

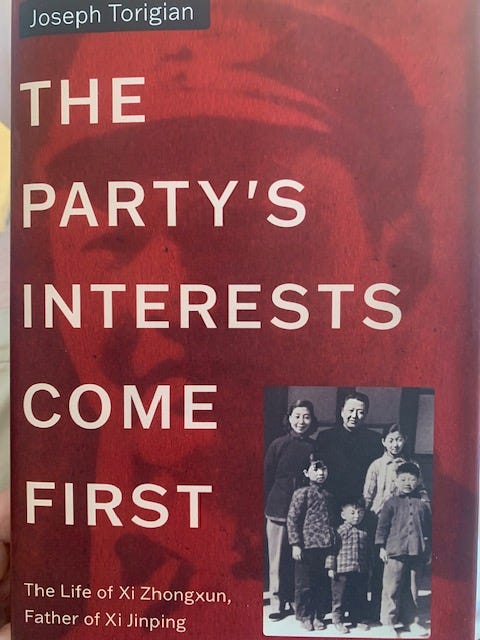

Sometimes, facts are most interesting for their absence. That’s certainly the case in chapter 28 of Joseph Torigian’s new political biography of Xi Jinping’s father Xi Zhongxun (10 years in the making!) … the chapter that deals with Xi Zhongxun’s role during the weeks of protests on Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the spring of 1989.

(My review of the book in Foreign Policy).

In the meantime, since today is June 4, 2025, the anniversary of the bloody crackdown, I thought I would delve deeper into what Torigian has found — or more accurately, not found, regarding Xi Zhongxun’s role during the crisis.

The title says it all….

Chapter 28, “Tiananmen Square” lays out the increasingly urgent efforts of older, more sober members of the National People’s Congress to both preserve the momentum of reform and preserve the lives and safety of the crowds in the Tiananmen Square who were radicalizing in the face of Communist Party refusal to acknowledge any of their demands. It’s an interesting look at the escalation of the crisis.

But where was Xi Zhongxun, supposed reformer? Well, no-where, it seems. He just kind of disappears. (Believe me, Torigian is thorough in his research). Xi Zhongxun makes some documented appearances but he’s clearly NOT among the people trying to salvage the deteriorating situation. He was, essentially, second-in-command at the National People’s Congress, at least by title, so his role was very relevent at this stage of the crisis, in April-May 1989.

This is an important question because many of China’s most influential liberals pitched Xi Jinping as a potential liberal reformer to their domestic and foreign networks around 2010-2012, when he was on the cusp of power. The argument at the time was that Xi père had been a liberal, so Xi fils would be too. It was an argument that got quite a lot of traction at the time, and (whether intentionally or not) it significantly muddied the early understanding of Xi’s administration.

Many of these liberals were allied with the administration of Hu Yaobang, the ousted premier whose death kicked off the protests, and many were quite prominent in the late 1980s. They would also have been very aware of the actions at the National People’s Congress. By the 2000s, we journalists always called the NPC China’s “rubber-stamp legislature” but it legitimately played an active and independent role in the late 1980s and 1990s on issues such as civil rights, the environment and economic reforms.

Torigian notes some public appearances by Xi Zhongxun and cites contemporary records — primarily the diary of reformist godfather Li Rui — indicating that he was anxious and agitated. So maybe he bowed out of the action, in some sort of emotional crisis (he was prone to meltdowns), or maybe he was working behind the scenes to rein everyone in, or maybe he was just a good party apparatchik, making sure that he stayed exactly in step with whatever the Party wind seemed to be blowing. It’s not clear.

What is clear is that Xi Zhongxun does not seem to have played any significant role amongst the liberal reformers during this time of acute crisis, and they would have known that when they trotted out the tale that he was an active opponent to the Tiananmen crackdown.

Granted, 20 years passed between the Tiananmen crisis and the whispers that (don’t worry!) Xi Jinping would be a reformer. Marinading in the fear and resentment and nostalgia that comes with being on the losing side of a political battle, especially given that old men’s memories fade, maybe they just forgot. Maybe they perked up when a rising political star had some association with their side. Maybe they projected a lot of things onto him that he passively encouraged; maybe they just felt important that people were asking. Maybe they didn’t want to admit that they didn’t know.

At any rate, the value of Torigian’s book is it sets the record straight.

Early on I was impressed by his cultural hubris — he not only looted the libraries of leading bibliophiles (some of whom I got to know from the late 1970s) but also had Rong Bao Zhai at Liulichang display some of his guohua paintings, signed Lu Chishui 魯赤水, a reference to his origins in Shandong and one of his many 號 or literary names. My old mentor Simon Leys purchased a couple of those works during his time in Beijing …

Cool piece, I added some thoughts here: https://youshu.substack.com/p/xi-zhongxuns-stance-in-may-1989