Rare Earths are more like Cinnamon than like Crude Oil

A better analogy would help us hash out our industrial policy

Trade disputes over rare earths are back in the news, which means gnashing of teeth over the lack of a solution to a strategic vulnerability is back in the news. In the past several days I’ve read and heard a lot of discussion about rare earths, and noticed a lot of misconceptions.

So, here’s a humble proposal to shift the way we frame the issue, from crude oil to…. Cinnamon. I think it might help.

First of all, the basics: Rare Earths are a group of 17 metals, some rare some not, all of which are found in globally significant quantities in one of two regions of China: the area around Baotou, in Inner Mongolia, and the area around Ganzhou, in southern Jiangxi Province. They are used in a variety of high-tech industrial applications – magnets, sensors, touch screens, etc. Broadly speaking, the ones around Baotou are less valuable and found in larger quantities, those around Ganzhou are more valuable and in smaller quantities.

Think for a second about the typical American spice rack. It’s divided into herbs, which are dried, crushed leaves of plants that grow well in Europe or the Mediterranean, and more exotic spices from tropical plants, most of which originated in the Spice Islands of Indonesia. In rare earth terms, the Baotou deposits are like herbs and the Ganzhou deposits are like cinnamon or nutmeg, which are some of the most expensive commodities in the world, on a per-tonne basis.

There are also rare earths deposits elsewhere in the world. They tend to feature just a few of these metals, not the full range as in China’s two regions, and in smaller quantities. Also, rare earths mining is often quite toxic, and polluting.

For more on rare earths,

was kind enough to unearth a 2019 Financial Times article by and myself, which still holds up pretty well as a primer for today, I think. One thing I would add is that although we call rare earths “metals”, they aren’t refined into hard gleaming ingots like normal metals. Instead, they are smelted into a kind of dry paste, molded into ingot shapes. I had one from Baotou on my Reuters desk for a while (a gift from colleagues Chris Buckley and David Gray) which disintegrated a little everyday, shedding a grey-green powder over my papers and everything. After a few months I decided that breathing or touching this powder on a daily basis was probably not healthy so I threw it out.Anyway, because rare earths are geologically concentrated in China, which regulates export volumes, people tend to respond to the periodic trade crises with talk of breaking China’s ‘monopoly’ or building ‘strategic reserves’. The favored analogy is to crude oil, in both Chinese and American discourse on the topic. Saudi Arabia has the world’s most important deposits, true, but oil is produced in lots of other countries, and strategic petroleum reserves have turned out to work fairly well in cushioning supply shocks, so lots of nations have invested in them.

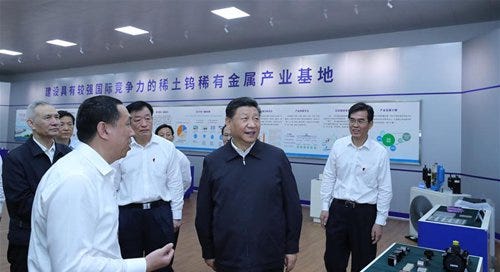

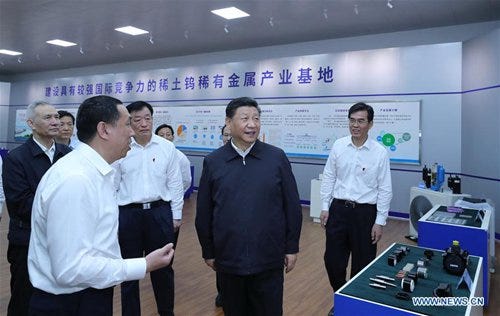

Xi Jinping in Ganzhou in 2019, during the first trade war - rare earths is an issue of industrial policy and national optics, more than trade. (Photo credit Xinhua)

However, using crude oil as a mental framework for rare earths results in lots of misconceptions, because fundamentally, rare earths aren’t just a raw materials issue, they are a supply chain issue.

Onward and upward with the cinnamon analogy!

Let’s say, someday in the future, all imports to the United States are banned. You want a gingerbread cake for little Johnny’s birthday, but the store-bought ones are $200 a pop. So, you decide to make one.

You gather your ingredients…. Luckily flour comes from wheat, which is grown in Nebraska, you’ve got sugar (thanks, Hawaii!) and powdered ginger, because ginger grows just fine in cool rich dirt of the northern Midwest. But what about cinnamon? Cinnamon grows in Indonesia. You cannot just “move production” of cinnamon by planting a tree in your backyard.

This being a point of dissatisfaction among other parents wanting to make birthday cakes, the White House has issued a special import exemption for cinnamon. The Indonesians (who are plenty annoyed about the US import ban) have agreed to a large shipment, just this once.

Stripping the cinnamon bark - still not ready for your cake. Photo credit: Tripper_nature

Hundreds of trunks of cinnamon trees arrive and are stacked in a large warehouse near Long Beach, CA. Now what? You still can’t bake your cake. Even if someone puts one of those cinnamon trunks into a woodchipper, you can’t bake the cake. You need it in a form of stabilized powder that will mix well and not clump. Also, you need the cinnamon in a precise ratio to nutmeg, another powder imported from Indonesia.

This is the thing with rare earths. The deposits are where they are, just like cinnamon trees grow where they grow. But even if the US devoted lots of money to investing in mines elsewhere or building rare earth stockpiles, it will not solve the problem, because very few companies need rare earths in their initial processed form. What they need is the intermediate products made from rare earths, to plug into their supply chain.

Again, with the cinnamon analogy. Almost no-one wants a log from a cinnamon tree. Some people might want the bark, but only in a form that’s been processed and dried into that little curl. Most bakers want the highly-processed powder. Some consumers want the powder pre-mixed in a set ratio with nutmeg and sugar and sold as ‘pumpkin spice’.

The rare earths supply chain is where things get really complex, from the point of view of trade and industrial policy. Traditionally, almost all of that intermediate supply chain was in Japan, which China saw as a strategic vulnerability. So, with carefully applied limitations on exports of intermediate product and tax incentives, plus the huge electronics industry that moved to China because of low wages and is now poised to produce the latest high-tech products, China has gradually assembled most of that supply chain onshore.

Back to the cinnamon analogy. We can build strategic stockpiles of tree trunks, but then we’d have to create a whole supply chain of grinders, driers, processors, little glass bottles, plastic bottle caps, etc to commercialize it to the various forms in which consumers want to add cinnamon to their baking process, whether the end product is chicken tagine or gingerbread cake or pumpkin spice latte.

In other words, we treat rare earths like a trade problem that can be solved by stockpiling (or like some sort of morality play, that can be solved by nationalistic outrage) but really, it’s a problem of 1> mining and geology; 2> trade quotas and price arbitrage; 3> very complex industrial value-added chains, further divided into intermediate processes, manufactured B2B products, like rare earth magnets for EV engines, or final consumer-facing products, like infrared military sensors.

Does framing rare earths as cinnamon help us to a solution to the fact that China has this stuff, and we want it? At least it helps us evaluate the pros and cons of potential solutions.

Yes, people can invest in mines elsewhere (cinnamon trees grow in Madagascar) but the mix of metals derived from them won’t be the full slate that comes from China. Importantly, whole processing chains need to be worked out, otherwise you just ship the concentrate to China to integrate into the supply chains there, which means you have just spent a lot of money on a high-cost mine without solving your strategic problem.

Commercial stockpiles. Most companies that process intermediate products involving rare earths do this already, as part of their supply and price risk management. You can supplement with national strategic stockpiling, as people often discuss for the Dept of Defense, but since they aren’t the ones deciding which of the 17 rare earths companies will need, it’s a crude tool. Also, strategic stockpiling raises the price of rare earths, thus reducing the commercial competitiveness of companies that aren’t in China.

New materials R&D to work out substitutes or lower quantities. This reduces vulnerability to the flow of rare earths from China, but doesn’t solve the manufacturing chain issues. Money is already flowing towards this.

China+One manufacturing strategy. Japan and Korea have significant China supply chains, and they also have spent a lot of time and money over the past decade and a half building parallel supply chains elsewhere in Southeast Asia, so if they have disruptions from China, they have ready-to-go alternatives. Japanese and Korean conglomerates famously take the long view, while in the US, investors’ interests are separated from manufacturers’, leading to an obsessive focus on quarterly profits and maximum profit extraction that doesn’t lend itself to creating supply chain redundancy. Can we change this corporate culture?

Industrial policy. China’s dominance today – not just in the geological deposits but also in the rare earths processing chain – is due to decisions taken in the early 2000s, when a few Chinese policy wonks deep in the industrial ministries argued that it was a mistake to shovel these valuable metals out the door in the form of cheap raw materials sold in bulk. It took TWENTY YEARS of intelligently applied quotas, tariffs, environmental crackdowns, subsidized industrial upgrades and an explosion in new tech applications, many developed in Japan, Korea or America but manufactured in China, to get to where we are today. This isn’t something that you negotiate in Geneva on Sunday and then eliminate by Tweet on Thursday.

There are definitely American policymakers who are pushing for these value chains to be recreated in the US – my point is that it would require decades of sustained industrial rejig, because we aren’t talking a single factory here. We are talking about thousands of discrete processes and thousands of intermediate and final products, potentially. Isolating just a few to receive state subsidies tends to result in a boondoggle of subsidy fraud and non-commercially competitive products. Also, there’s a long intermediate stage where we may manufacture some things in America but the supply chain still needs to get components from elsewhere (this is what free trade is all about). Take rare earth magnets, for instance, a hot topic in the latest trade disputes. They are a finished product from China, that is then assembled into a Made-in-America car.

To my mind, the China+One route is probably the best policy to pursue, but it does require a significant corporate cultural change in addition to a consistent and long-term trade and industrial policy in Washington. Currently, we have a national case of ADHD, in both corporations and in policy.

In any scenario, little Johnny will be a teenager before he gets his cake.

Great piece! I'll add the point I mentioned earlier with a comment here:

> ... while in the US, investors’ interests are separated from manufacturers’, leading to an obsessive focus on quarterly profits and maximum profit extraction that doesn’t lend itself to creating supply chain redundancy. Can we change this corporate culture?

It's not really just corporate culture. We literally don't have corporate entities in the right places to invest deeply in this. Maybe "all US corporates that need rare earths" together could be a block, but they don't coordinate in that way.

That goes a bit into industrial policy—I see a lot of interesting technologies from universities that COULD go towards the refining AND processing. I've seen one out of Berkeley that can do so on a really interesting modular/micro level. We didn't invest in them. They aren't economical vs. Chinese entities that have scale and don't need an "Easy Bake Oven" version of what they have. Now, the US has put money into companies like them (and them, I believe)—but it stops after R&D and moving into commercialization.

That might not have mattered as much in a globalized world, but it sure as hell matters now that the US really can't build anything. And, you know, tensions.

We literally have advanced US tech companies in our portfolio, say in advanced batteries... that are helping major Chinese companies become much more technologically advanced vs. US ones. But what's the alternative? You could have US IP/tech in Chinese companies... or you could have no US IP/tech, and the Chinese companies just do what they do, because that's their market in the current environment.

Thanks. I remember this issue from last time, and was wondering why it came up again - there are big deposits in Canada, after all. But the point about refining helps to clarify things a bit.